It is February 1945. Soldiers in the Soviet Eighth Guards Army stand in silence as they observe the rays of the morning sun glisten on the icy waters of the Oder River. Among them is the war correspondent Vasily Grossman Vasili has covered the war since The Battle of Moscow, and like his comrades in arms, he has counted every river he has crossed since the advance westward from the Volga at Stalingrad.

By early 1945, Hitler's Third Reich was on its last legs. While the Allies prepared to make a dash across the Rhine, in the east, the Soviet army was advancing toward the German border at lightning speed. As its armies closed in on Berlin, its men vowed to take revenge for the death and destruction brought upon the Motherland.

Hitler however, refused to go down without a fight, forcing his people into one last cataclysmic bloodletting that would only end when the hammer and sickle finally flew above the Reichstag, and the Führer Lay Dead In The Bunker.

1944 had been nothing short of a disaster for the Germans on the Eastern Front, following the annihilation of Army Group Center. The seemingly unstoppable Red Army had pursued the Wehrmacht all the way to the gates of Warsaw. In the south, Romania and Bulgaria had capitulated and switched sides, while Hungary was on the brink of collapse as Soviet armies laid siege to Budapest.

Unwilling to admit defeat, Adolf Hitler Now made the momentous decision to deploy his final armored reserve to relive the city's Defender and secure Hungary's oil Fields. This, as it turned out, was exactly what the Soviet High Command, better known as the Stavka, had hoped for. By increasing pressure on the Hungarian front, Stalin and his advisors forced the Germans into moving their vital armored reserves from Poland. Meanwhile, three Soviet fronts, totaling some 2.5 million soldiers, prepared to make a dash across the Vistula River around Warsaw and drive straight toward Berlin. Fueled by a desire for revenge, Stalin's armies began their offensive on January 12th. Within days The outgunned Defender were force into frenzied Retreat on the 15th General Heinz Guderian pleaded with hitler to send every available unit East, The Fuhrer in turn made great promises in the form if two SS Panzerkor recently withdrawn from ardenne however rather than arriving to salvage the situation they were thrown into yet another one Hitler pipe dream in Hungary lacking sufficient mobile reserve, the bulk of the ill-fated German Defender were incircled and destroyed as the casastrophe unfold the berlin radio broadcast apocalyptic news bulletins which compared the advancing Red Army

To the Mongol hordes, the Huns, and the Tartars, who were out to bring total destruction and the end of civilization, the advancing Red Army was viewed with similar dread. Driven by fear, a growing mass of refugees began a long and deadly march across the icy roads leading westward in hopes of escaping the jaws of Soviet vengeance. However, the dreaded Red Horde was moving at lightning speed, and by the end of January, its armies had advanced some 500 kilometers (nearly 311 miles) to the banks of the river just 60 kilometers (37 miles) from Berlin. The rapid advance, however, had stretched the Red Army's logistics to their limit, and heavy resistance in East Prussia left Marshall Georgy Zhukov's forces vulnerable to a counterattack from German troops massing in Pomerania. As a result, the Stavka decided to halt the final assault on Berlin until the flanks were secured. By mid-April, the Red Army had reached the Oder-Neisse River line on a front that stretched from Stettin in the north to the Czech border in the south. The eyes of the world were now converging on Berlin as Stalin's army prepared for their final act of vengeance that would eradicate Nazi Germany once and for all.

Although the Allies promised to leave Berlin to the Red Army, the ever-paranoid Stalin still urged haste in the capture of the city. The final plan called "for a three-pronged attack" on the Berlin axis to encircle and capture the city within 12 to 15 days, then move to meet the Allies at the Elbow River. Zhukov's First Belorussian Front would be at the center of the thrust, while Marshall Ivan Konev's First Ukrainian Front to the south was set to attack across the Neisse River in the direction of Potsdam and Dresden. Finally, Marshall Constantine Rokossovsky's Second Belorussian Front would tie down German forces to the north in the Stettin-Schwedt sector to prevent them from reinforcing Berlin.

Having become accustomed to fighting on wide-open terrain, few in the Red Army had much experience in large-scale urban street fighting. It was up to General Vasily Chuikov's Eighth Guards Army, veterans of the Battle of Stalingrad, to distribute pamphlets on urban warfare, while special combined-arms task forces were formed. Red Army engineers, for their part, worked day and night to construct thousands of wooden assault boats to cross the Oder and Neisse Rivers. To achieve this, Soviet planners had to find a way to move 29 armies over hundreds of kilometers to create shock groups capable of penetrating the German lines in areas only 2.5 to 10 kilometers wide. When all was said and done, the Red Army would advance on Berlin with some 2.5 million men, 6,250 tanks and self-propelled guns, and 7,500 combat aircraft.

Aiming to make the invaders bleed for every inch of German soil, the Wehrmacht constructed a series of well-entrenched defensive lines that barricaded the approach to Berlin. Manning these positions were the remnants of Army Group Vistula, the Fourth Panzer Army, and the Berlin garrison. Combined, this force consisted of 750,000 German soldiers supported by 1,519 tanks and assault guns, 9,303 artillery pieces, and 2,200 aircraft. However, these numbers looked more impressive on paper than they did in reality, as virtually all formations were understrength. Although many units were led by battle-hardened veterans of the Eastern Front, their rank and file often consisted of a mix of wounded and inexperienced soldiers, and even boys from the Hitler Youth.

Moreover, some 60,000 of the defenders came from untrained and poorly armed Volksturm militia battalions. The infantry could not rely much on its armored and air assets either, as the Germans lacked the fuel reserves to support what was otherwise a considerable force of fighting vehicles for any extended period of time. Morale was also at an all-time low; most soldiers suffered from malnutrition and poor hygiene. Aside from the most fanatical Nazis, few still believed in a final victory. Even so, every effort was made to convince the men that the much-anticipated Wunderwaffe would still turn the tide of the war and that peace talks with the Western Allies were soon to bear fruit. But if these motivations had only marginal success, the widespread fear of Soviet vengeance and barbarism drove even the most cynical to continue fighting. On April 12th, the Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra (Berlin Philharmonic) gave its last performance. Among the music played was Richard Wagner's Ride of the Valkyries. Four days later, another type of orchestra began to play as thousands of Katyusha rocket launchers and field guns from Zhukov's front opened fire on the first German defensive line along the Seelow Heights. Miles away, in Berlin's eastern suburbs, houses began to shake as terrified citizens gathered in the streets to listen to the start of the coming storm.

A stunned Russian engineer described the unfolding spectacle. The searchlights, intended to blind the enemy, instead reflected off the smoke-filled air, obscuring the advancing infantry. As a result, units lost contact with each other, and Soviet artillery and aircraft began attacking friendly formations. Worse still, German intelligence had prior knowledge of the coming offensive, and many of the first-line troops had been evacuated to safety in the rear. What ensued was nothing less than what a member of the Grossdeutschland Guard Regiment described as a "slaughterhouse." Countless soldiers were cut down as they struggled to advance across the floodplains and through German minefields. In other sectors, too, the attacks were repelled as Soviet forces attempted to cross the Oder River. Sensing danger and becoming increasingly agitated, Zhukov ordered his 2nd Tank Army to attack at once. However, most of the infantry, artillery, and supply vehicles were still trying to make their way to the front, causing the tank armies to become hopelessly stuck in endless traffic jams. Even when the lead armor finally approached the heights, they found themselves ambushed by concealed 88mm gun emplacements, Tiger I tanks, and deadly Panzerfaust recoilless anti-tank launchers.

Unsurprisingly, Zhukov's decimated men made little progress by the end of the first day. It would take three days and countless more dead before his armies finally forced their way through the final defensive line. Naturally, Stalin was infuriated, but he could rest easy knowing that Konev's front to the south had seen more success. By the end of April 18, Konev’s tank armies were racing toward Berlin. Lacking sufficient reinforcements and ammunition, the surviving defenders in both sectors were forced into a headlong retreat. With the German defensive lines in the south and center broken, and with their forces in the north still tied down in heavy fighting, the road to Berlin lay open. Lacking the supplies to continue fighting, German morale visibly began to collapse. Thousands of encircled soldiers surrendered, while masses of stragglers, deserters, and refugees made their way into the doomed city. All the while, an increasingly delusional Hitler continued to demand fanatical resistance until the bitter end.

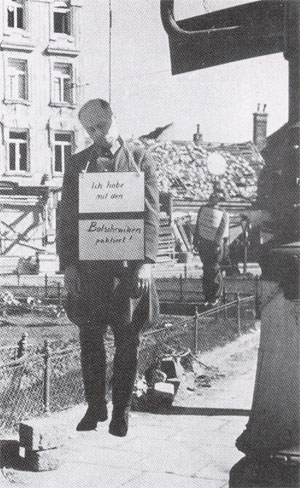

On April 20th, the Führer's birthday was interrupted by Soviet artillery shelling Berlin's northeastern suburbs, forcing its citizens to flee into cellars. Zhukov's and Konev's tank armies began a frantic race to the city's outskirts. Meanwhile, many senior officials of the Nazi Party engaged in a similar competition, each seeking permission to be the first to leave the city. The soldiers on the ground enjoyed no such privileges, and those who tried to flee or showed signs of cowardice were summarily hanged throughout the city, with messages such as "I was a coward and a deserter" dangling from their chests. The next morning, Soviet artillery launched a frenzied barrage into Berlin's city center. Meanwhile, the remnants of General Helmuth Weidling's 56th Panzer Corps of the 9th army prepared for the final desperate defense.

While being mercilessly strafed by Soviet aircraft, other remnants of the German defense attempted in vain to stop Zhukov's armies from pushing into the city from the southwestern and northern flanks. However, its depleted units could only delay the enemy, and Zhukov's and Konev's forces both reached the city's outskirts that evening.By nightfall, the once-formidable German defenses had crumbled under relentless Soviet pressure. As artillery fire illuminated the darkened skyline, desperate German units mounted last-ditch counterattacks, only to be overwhelmed by the sheer force of the advancing Red Army. Civilians and soldiers alike braced for the inevitable street-to-street combat, as Soviet troops poured into the city, determined to bring the brutal conflict to its final chapter.